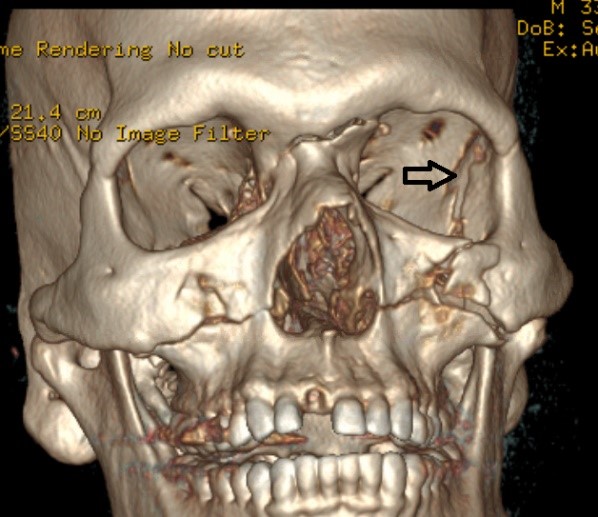

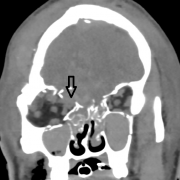

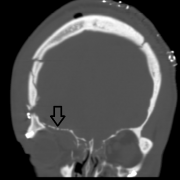

Midface and Zygoma Fracture

The surgical treatment goal in repairing midface fractures is to restore masticatory function and orbital function and to restore facial form. Restoration of facial buttresses and dental occlusion restores function and facial width and projection. Restoration of orbital volume and release of incarcerated orbital tissues restores orbital form and function. Midface fractures require a comprehensive timing and treatment plan for each fracture. Lateral canthotomy with inferior cantholysis is a quick way to decompress an orbit involved in midface trauma. ZMC and orbit are considered together during repair and should be best managed when swelling has subsided. Soft tissue replacement following surgical access is essential to prevent esthetic complications.

After completing this module the physician will be able to:

- Discuss the initial assessment and management of life-threatening and orbit-threatening issues often seen with severe midface face trauma.

- Identify the boundaries of the bones of the midface to include the maxilla, zygoma, nasal bones, orbit bones, frontal bone and pterygoid bones.

- Discuss the structural bony anatomy of the midface and describe its system of vertical and horizontal buttress.

- Describe the anatomy of the zygoma and the articulations associated with complex fractures of the zygoma.

- Describe the common injury patterns of midface fractures and include the LeFort classification, zygomaticomaxillary (ZMC) fractures and orbital fractures.

- Diagnose midface and zygoma fractures by patient symptoms, physical exam presentation, and radiographic findings.

- Accurately identify fractures using CT and 3DCT radiographic findings to prescribe the appropriate treatment required for midface and zygoma fractures.

- Explain the soft tissue approaches for surgical repair of the midface.

- Describe the repair sequence of complex panfacial trauma.

- Explain the dental and occlusal considerations in midface fractures.

- Discuss the surgical technique necessary to reconstruct the three-dimensional skeletal structures to restore the face to its original width, height, and sagittal projection and occlusion.

- Describe complications associated with midface and zygoma fractures and discuss treatment for bleeding, malunion, nerve injury, eye and lacrimal injury, and malocclusion.

Learner must Sign In to access AAO-HNSF education activities.

- Annual Meeting Webcast (AMW):